Portal:History of science

The History of Science Portal

The history of science covers the development of science from ancient times to the present. It encompasses all three major branches of science: natural, social, and formal. Protoscience, early sciences, and natural philosophies such as alchemy and astrology during the Bronze Age, Iron Age, classical antiquity, and the Middle Ages declined during the early modern period after the establishment of formal disciplines of science in the Age of Enlightenment.

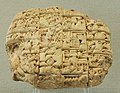

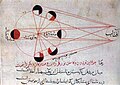

Science's earliest roots can be traced to Ancient Egypt and Mesopotamia around 3000 to 1200 BCE. These civilizations' contributions to mathematics, astronomy, and medicine influenced later Greek natural philosophy of classical antiquity, wherein formal attempts were made to provide explanations of events in the physical world based on natural causes. After the fall of the Western Roman Empire, knowledge of Greek conceptions of the world deteriorated in Latin-speaking Western Europe during the early centuries (400 to 1000 CE) of the Middle Ages, but continued to thrive in the Greek-speaking Byzantine Empire. Aided by translations of Greek texts, the Hellenistic worldview was preserved and absorbed into the Arabic-speaking Muslim world during the Islamic Golden Age. The recovery and assimilation of Greek works and Islamic inquiries into Western Europe from the 10th to 13th century revived the learning of natural philosophy in the West. Traditions of early science were also developed in ancient India and separately in ancient China, the Chinese model having influenced Vietnam, Korea and Japan before Western exploration. Among the Pre-Columbian peoples of Mesoamerica, the Zapotec civilization established their first known traditions of astronomy and mathematics for producing calendars, followed by other civilizations such as the Maya.

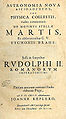

Natural philosophy was transformed during the Scientific Revolution in 16th- to 17th-century Europe, as new ideas and discoveries departed from previous Greek conceptions and traditions. The New Science that emerged was more mechanistic in its worldview, more integrated with mathematics, and more reliable and open as its knowledge was based on a newly defined scientific method. More "revolutions" in subsequent centuries soon followed. The chemical revolution of the 18th century, for instance, introduced new quantitative methods and measurements for chemistry. In the 19th century, new perspectives regarding the conservation of energy, age of Earth, and evolution came into focus. And in the 20th century, new discoveries in genetics and physics laid the foundations for new sub disciplines such as molecular biology and particle physics. Moreover, industrial and military concerns as well as the increasing complexity of new research endeavors ushered in the era of "big science," particularly after World War II. (Full article...)

Selected article -

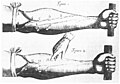

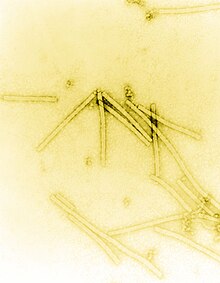

The history of virology – the scientific study of viruses and the infections they cause – began in the closing years of the 19th century. Although Edward Jenner and Louis Pasteur developed the first vaccines to protect against viral infections, they did not know that viruses existed. The first evidence of the existence of viruses came from experiments with filters that had pores small enough to retain bacteria. In 1892, Dmitri Ivanovsky used one of these filters to show that sap from a diseased tobacco plant remained infectious to healthy tobacco plants despite having been filtered. Martinus Beijerinck called the filtered, infectious substance a "virus" and this discovery is considered to be the beginning of virology.

The subsequent discovery and partial characterization of bacteriophages by Frederick Twort and Félix d'Herelle further catalyzed the field, and by the early 20th century many viruses had been discovered. In 1926, Thomas Milton Rivers defined viruses as obligate parasites. Viruses were demonstrated to be particles, rather than a fluid, by Wendell Meredith Stanley, and the invention of the electron microscope in 1931 allowed their complex structures to be visualised. (Full article...)

Selected image

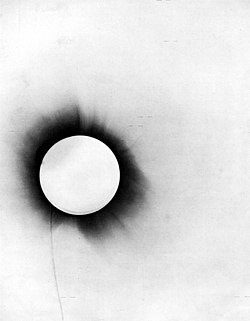

During the solar eclipse of May 29, 1919, several teams of scientists attempted to verify Einstein's prediction of the bending of light around the sun using photographic measurements. This negative, taken from Arthur Eddington's report of the expedition to the African island Príncipe, was presented as part of a successful test of general relativity, based on the positions of stars near the eclipsed sun. The original caption reads:

- In Plate 1 is given a half-tone reproduction of one of the negatives taken with the 4-inch lens at Sobral. This shows the position of the stars, and, as far as possible in a reproduction of this kind, the character of the images, as there has been no retouching. A number of photographic prints have been made and applications for these from astronomers, who wish to assure themselves of the quality of the photographs, will be considered as as far as possible acceded to.

Did you know

...that the travel narrative The Malay Archipelago, by biologist Alfred Russel Wallace, was used by the novelist Joseph Conrad as a source for his novel Lord Jim?

...that the seventeenth century philosophers René Descartes, Baruch Spinoza, and Gottfried Leibniz, along with their Empiricist contemporary Thomas Hobbes all formulated definitions of conatus, an innate inclination of a thing to continue to exist and enhance itself?

...that according to the controversial Hockney-Falco thesis, the rise of realism in Renaissance art, such as Jan Van Eyck's Arnolfini Portrait (pictured), was largely due to the use of curved mirrors and other optical aids?

Selected Biography -

Gottfried Wilhelm Leibniz (or Leibnitz; 1 July 1646 [O.S. 21 June] – 14 November 1716) was a German polymath active as a mathematician, philosopher, scientist and diplomat who is credited, alongside Sir Isaac Newton, with the creation of calculus in addition to many other branches of mathematics, such as binary arithmetic and statistics. Leibniz has been called the "last universal genius" due to his vast expertise across fields, which became a rarity after his lifetime with the coming of the Industrial Revolution and the spread of specialized labor. He is a prominent figure in both the history of philosophy and the history of mathematics. He wrote works on philosophy, theology, ethics, politics, law, history, philology, games, music, and other studies. Leibniz also made major contributions to physics and technology, and anticipated notions that surfaced much later in probability theory, biology, medicine, geology, psychology, linguistics and computer science.

Leibniz contributed to the field of library science, developing a cataloguing system (at the Herzog August Library in Wolfenbüttel, Germany) that came to serve as a model for many of Europe's largest libraries. His contributions to a wide range of subjects were scattered in various learned journals, in tens of thousands of letters and in unpublished manuscripts. He wrote in several languages, primarily in Latin, French and German. (Full article...)

Selected anniversaries

- 1539 - Birth of Christopher Clavius, German mathematician (d. 1612)

- 1561 - Death of Conrad Lycosthenes, French-born German philosopher and encyclopedist (b. 1518)

- 1655 - Saturn's largest moon, Titan, is discovered by Christiaan Huygens

- 1712 - Death of Nehemiah Grew, English naturalist (b. 1641)

- 1800 - Birth of Heinrich von Dechsen, German geologist (d. 1889)

- 1818 - Death of Caspar Wessel, Danish mathematician (b. 1745)

- 1946 - Birth of Maurice Krafft, French vulcanologist (d. 1991)

- 1952 - Birth of Antanas Mockus, Colombian mathematician

Related portals

Topics

General images

Subcategories

Things you can do

Help out by participating in the History of Science Wikiproject (which also coordinates the histories of medicine, technology and philosophy of science) or join the discussion.

Associated Wikimedia

The following Wikimedia Foundation sister projects provide more on this subject:

-

Commons

Free media repository -

Wikibooks

Free textbooks and manuals -

Wikidata

Free knowledge base -

Wikinews

Free-content news -

Wikiquote

Collection of quotations -

Wikisource

Free-content library -

Wikiversity

Free learning tools -

Wiktionary

Dictionary and thesaurus